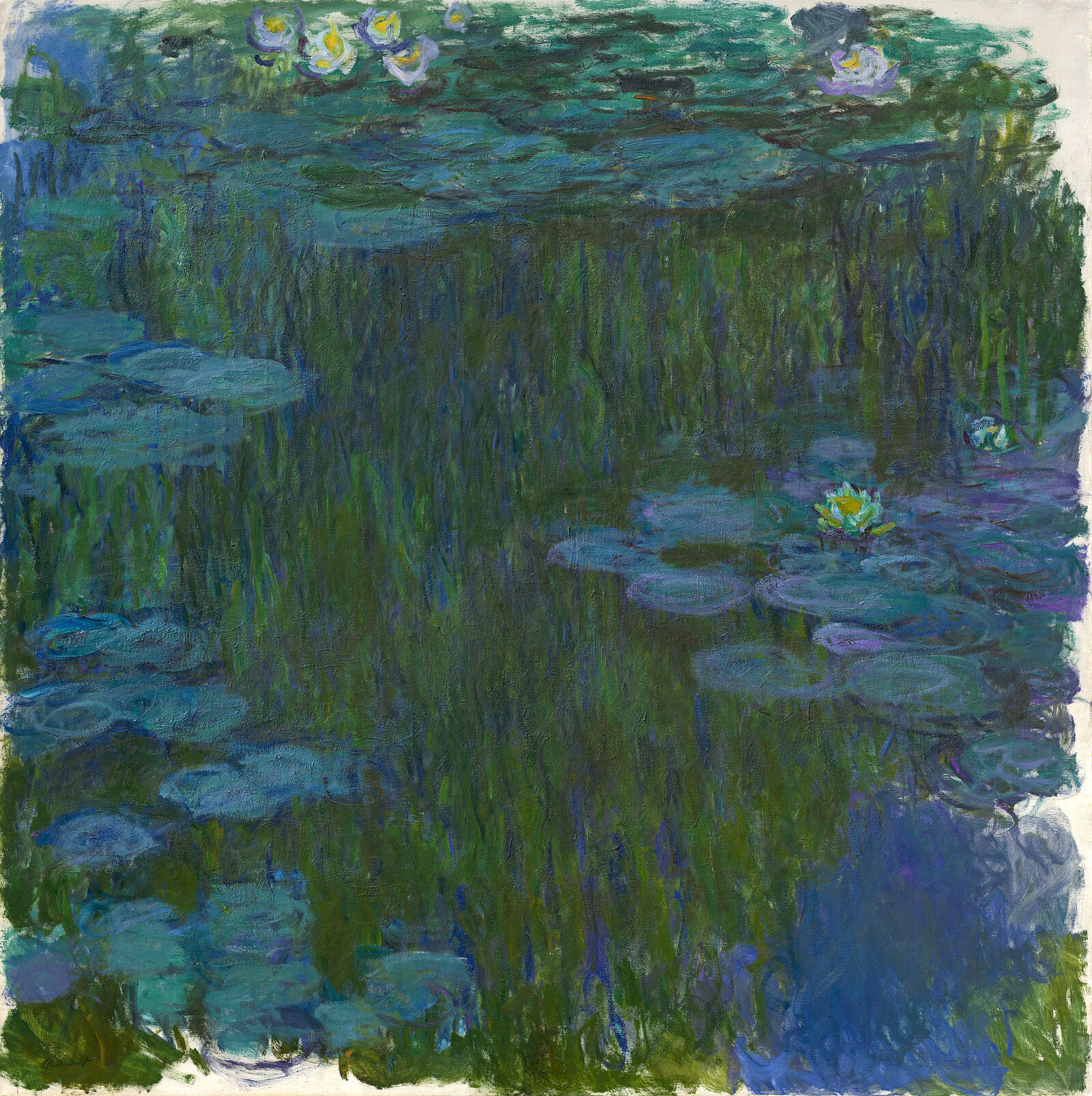

Claude Monet

Water Lilies, 1914–1917

On view

39 further works by Monet

Copy link

Oil on canvas, 200 x 200 cm

Stamped lower left: Claude Monet

Inv.-no. MB-Mon-33

In 1893 Claude Monet had a water garden designed in Giverny that was inspired by Japanese examples. For nearly thirty years he devoted himself almost exclusively to the motif of the water-lily pond. The lack of a horizon and spatial depth imparts an air of boundlessness. In this way, combined with his use of free brushwork and expressive colors, Monet became a pioneer of abstraction in the twentieth century.

Even before his move to Giverny, Claude Monet was a passionate amateur gardener, and the lovingly cultivated garden was an important motif in his artistic repertoire in both Argenteuil and Vétheuil. Not until Giverny, however, was he able to combine the practice of plein-airpainting with the amenities of a well-equipped studio. After acquiring the estate “Le Pressoir” (The Cider Press) in 1890, Monet first concentrated on the redesign of the “Clos Norman,” a cottage garden typical of Normandy with vegetables and fruit, surrounded by a wall. There he installed lavish flower beds, and from 1893 on he embarked upon an even more complex project with the creation of an opulent water garden. Monet had acquired a plot of land adjacent to his property, and there he installed an artificial pond. The pool, fed by running water, was ideal for cultivating both native and exotic plants including numerous species of water lily. Apart from thirty-seven works created in Venice in 1908, after 1903 Monet no longer painted outside his garden in Giverny. With more than two hundred documented variations, the Nymphéas constitute the most extensive series in his oeuvre of around 2,050 works and are now considered the very epitome of Impressionist painting. In a conversation with the writer Marc Elder in the 1920s, Monet stated: “It took me some time to understand my water lilies. I planted them purely for pleasure; I grew them with no thought of painting them. A landscape takes more than a day to get under your skin. And then, all at once I had the revelation—how wonderful my pond was—and reached for my palette. I’ve hardly had any other subject since that moment.”

This large square composition belongs to a series of around forty related images of water lilies, probably painted between 1914 and 1917. These works are distinguished by their expressive brushwork with broad textures and abstract color design. The conspicuous white areas at the edges of the canvas and the absence of a signature do not necessarily indicate that the work was unfinished or that Monet viewed it as an incomplete study. On the contrary, he often did not sign or date his works until they were ready to be sold or shown in an exhibition. With few exceptions, however, almost none of the works from this series of Nymphéas were exhibited during Monet’s lifetime, and only a single one was sold. The paintings remained in his studio in Giverny and became the property of his son Michel after his death. The film Ceux de chez nous (“Those of Our Land,” 1914) by Sacha Guitry includes an approximately two-minute sequence showing Monet by the pond, painting this work.

In 1955 the Museum of Modern Art in New York was one of the first museums to acquire a painting from this series, but it was destroyed by fire three years later. Other variations from this group of large-scale water lily pictures are now in the Portland Art Museum in Oregon and the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo. In the four-volume catalogue raisonné of Monet’s paintings compiled by Daniel Wildenstein, the painting in the Hasso Plattner Collection is listed as no. 1803 (vol. 4, p. 851).

Daniel Zamani

Impressionisten: Monet, Pissarro, Sisley, Vorläufer und Zeitgenossen, Kunsthalle Basel, September 3–November 20, 1949, no. 209

Claude Monet. 1840-1926, Kunsthaus Zürich, May 10–June 15, 1952, no. 114

Claude Monet: Nymphéas, Kunstmuseum Basel, July 20–October 19, 1986, no. 35

Monet in the 20th Century, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, September 20–December 27, 1998; Royal Academy of Arts, London, January 23–April 18, 1999, no. 60

Claude Monet 1840–1926: A tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, Wildenstein, New York, April 27–June 15, 2007, no. 57

Impressionism: The Art of Landscape, Museum Barberini, Potsdam, January 21–May 28, 2017, no. 68

Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature, Denver Art Museum, October 20, 2019–February 2, 2020

Monet: Orte, Museum Barberini, Potsdam, February 22–July 19, 2020, no. 128

Impressionism: The Hasso Plattner Collection, Museum Barberini, Potsdam, from September 5, 2020

n.d., Michel Monet, Giverny, inherited

from his father

1949, Private collection, acquired from the above

1982, Walter Schiess, Basel

December 3, 1991, Sotheby’s, London, lot 24, unsold

n.d., Private collection, Switzerland

April 2001, Art trade, acquired from the above

Claude Monet 1840–1926, exh. cat. Zurich 1952, no. 114

Denis Rouart and Jean-Dominique Rey, Monet: Nymphéas ou les miroirs du temps. Suivi d’un catalogue raisonné par Robert Maillard, Paris 1972, ill. p. 185

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 4, Lausanne 1985, no. 1803, p. 258, ill. p. 259

Claude Monet: Nymphéas. Impression, Vision, exh. cat. Kunstmuseum, Basel 1986, no. 35, p. 175, ill. p. 35

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet: Catalogue Raisonné. Werkverzeichnis, vol. 4, Cologne 1996, no. 1803, p. 851/52, ill. p. 851

Monet in the 20th Century, exh. cat. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 1998, no. 60, p. 60, 192, 218, 252, ill. p. 195

Claude Monet 1840–1926: A tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, exh. cat. Wildenstein, New York 2007, p. 57

Impressionism: The Art of Landscape, exh. cat. Museum Barberini, Potsdam 2017, no. 68, p. 18, 76, 158, 188, ill. p. 186, 197

Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature, exh. cat. Denver Art Museum, Denver 2019, no. 128, p. 71, ill. p. 253

Monet: Orte, exh. cat. Museum Barberini, Potsdam 2020, no. 128, ill. p. 253

Do you have suggestions or questions?

sammlung@museum-barberini.de.